Ütopik Algı Levhaları

Utopian Perception Boards

Evrim Altuğ, Şubat 2021

Ütopik Bürokratik sergi kataloğu

“Oku ve anlat.”

İlköğretim çağında maruz kaldığımız, belki ilk bürokratik buyruktu.

Önce (muhakkak içimizden, kimseye işittirmeksizin) bir şeyleri ezberleyecek, sonra kendi derme çatma kelimelerimize, şansımız, cüretimiz de varsa, eylemlerimize sevk ederek, aynı anlam ve ideale koşacaktık.

Bir şeyi ezberlemek, onun bizi sahiplenmesi, sırf kendine saklamasıyla eş değerdi. ‘Çıkar göster’ denildiği vakit, tek solukta telaffuzdan gocunmayacaktık. Onu ne kadar hatırlıyorsak, kendimizi kaybedene kadar ona tutunacak, onu savunacaktık.

Bu ikilemi, aynı şekilde, atlaslarda gözlerimiz önüne serili, bilumum fizikî ve siyasî haritaya aidiyet talebimizde de hissedip, durduk. Kimimiz doğrudan ülkesini, kimimiz dolaylı tümleç misali, hep gitmek istediği, düşlediğini seçip, parmağıyla koymuş gibi, o haritalarda kendini buldu.

Sonra bitmedi bu, kendimizi ne tam anlamıyla soyutlama, ne de somutlama halimizin, çetrefilli bir buket benzerini, altyazı ile görüntü, ya da ‘orijinal-dublaj’ veya ‘renkli-siyah beyaz’ ya da ‘naklen-banttan’ gelgitler arasında deneyimlemeye başladık.

Veya, Resim-İş, Müzik, Türkçe derslerinde hep, bir ‘direksiyon’ devraldık. Millî dünler, mevsimler, türlü yerel, ailevi ve beşerî örf ve âdetleri önce çizgiler, sonra boyalar, ardından notalar ve sözlerle tahayyül edip, ardından bunların hakikatine tahammül etmeye başladık. Ne müziğimiz, ne imgelerimiz, ne de kullandığımız kelimelerde, kendimize rastlayamadık…

Muhakeme vitesini hep otomatikte, ezbere ve sınıfta, bütünlemeye, ikmale bıraktık.

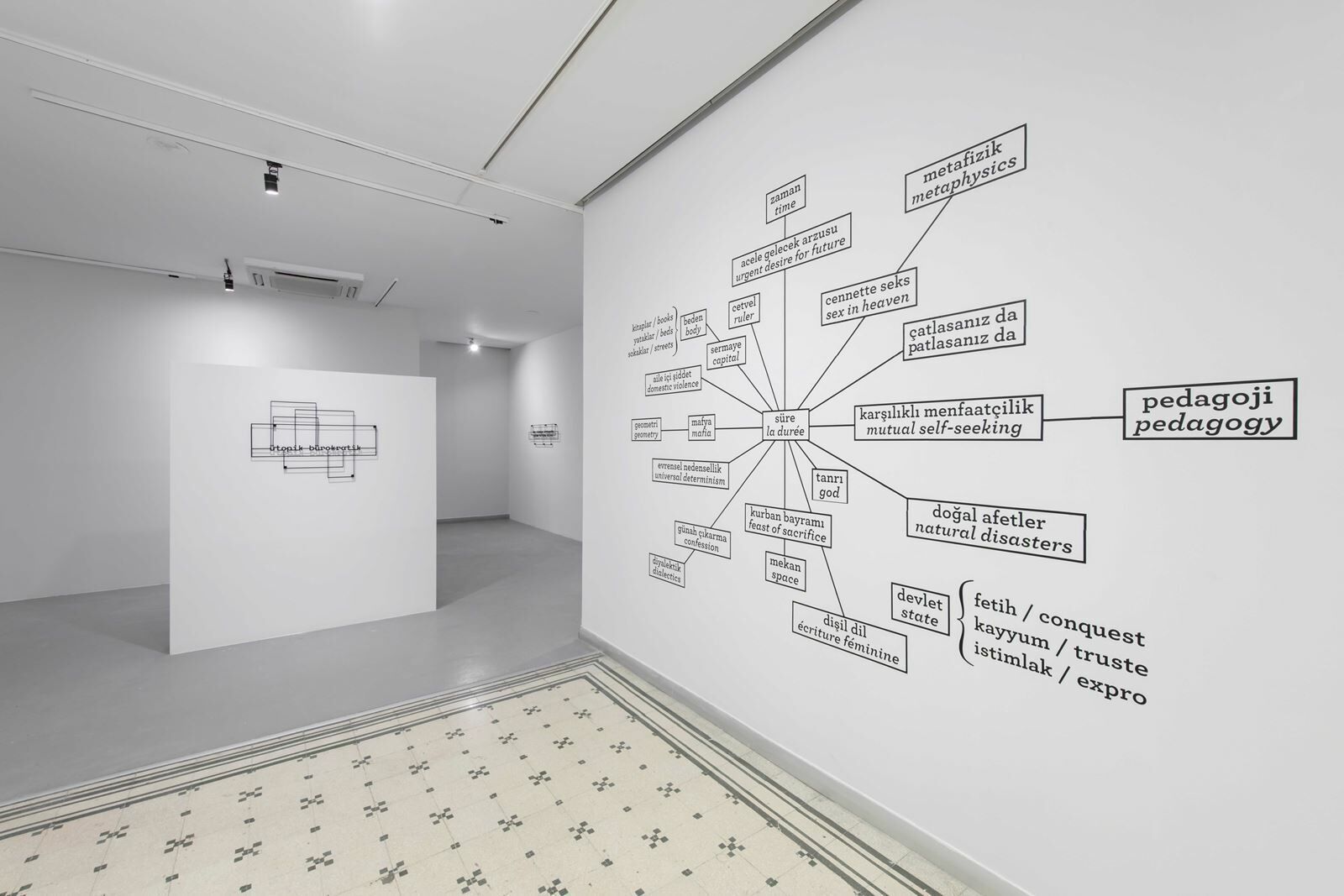

Memed’in Zilberman Istanbul’da yer bulan son yapıt dizisi ‘Ütopik Bürokratik’, hayat trafiğinin çileli haritasında bizi kendimizle yeniden karşı karşıya bırakmak adına bir dizi yönlendirme levhasını önümüze çıkarıyor.

Can Yücel’e, Ece Ayhan’a, Cemal Süreya’ya, Turgut Uyar’a, Orhan Veli’ye selam söyleyen, sözlüklere isyankâr bir grup ‘kafası bozuk’ kelime var önümüzde. Tümü, birkaç yönden okunaklı, anlatılmayı hak eder bir içerik vadediyor. Yönlendirmeyi değil, vesile olmayı önceliyor.

Biçimsel olarak rölyefleri, yazıtları da arkasına alan bu gür sesli, kavruk cüsseli demir levhalar, günümüz yeraltı şebekelerinin gittikçe soyuta yaklaşan şemalarını, ya da Modern sanatın Art Deco grafik nezaketini de bünyesinde barındırıyor.

Memed, giderek kavramsal bir berraklığa da yaklaşık, şiiri belki de bilinen en plastik malzeme olarak yâd ettiği bu serisi ile görsel, metinsel, semantik ‘kalıp’ların (İngilizcede ‘pattern’ denilen mefhumun) dışına nasıl çıkabileceğimize, onlarla ne kadar baş başa kalabileceğimize dair, manzum müdahalelerde bulunuyor.

Kalıp, Osmanlıca dilinde ‘resim’, numune’, ‘örnek’, ‘kalıp’ gibi ifadelere karşılık gelirken, günümüzdeki yaygın anlamı ile ‘desen’e de hizmet ediyor. İşte, bu her biri Türkçe bu tüzel kişilik ‘desen’i vesilesiyle Erdener, bireysel tahayyül sermayelerimiz ve gönüllü katılım taleplerimiz doğrultusunda, her birimizi kolektif, iyimser bir yapının da ütopik hafriyatına davet ediyor. ‘Basmakalıp’ ne varsa, aksi istikametteki bu centilmen, ‘asma-kalıp’larda birer hayal sarmaşığı gibi özgürce, birbirinden türüyor; bizlerin zaman ve mekânlarına edepsizce, gelişigüzel tünüyor.

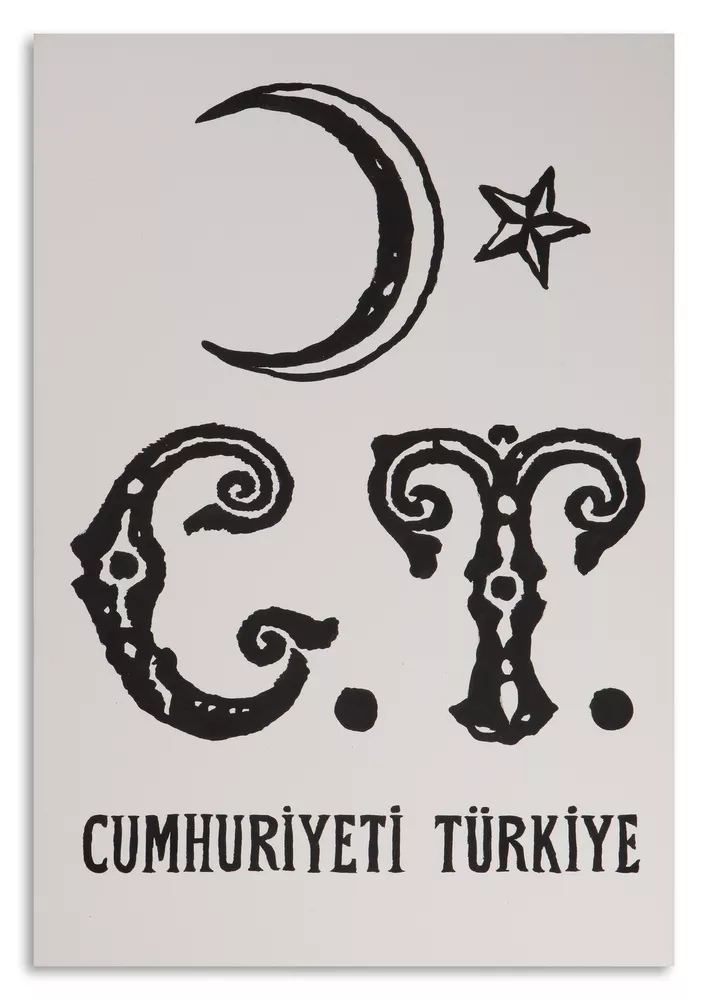

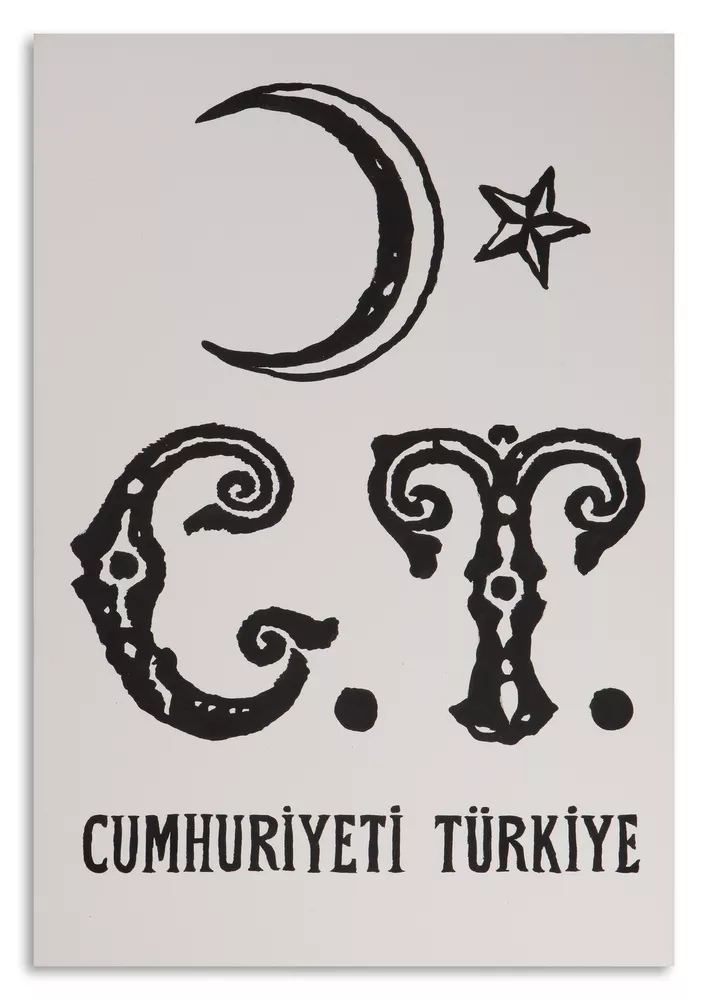

Ütopik Bürokratik, Memed’in daha önceki ‘ Cumhuriyet-i Türkiye’ (2010), ‘

Cumhuriyet-i Türkiye’ (2010), ‘ 1915 - Türkiye’de Yaşayan Ermenilere Adanmıştır’ (2012), ‘

1915 - Türkiye’de Yaşayan Ermenilere Adanmıştır’ (2012), ‘ Kölelik Müzesi’ (2015), ‘

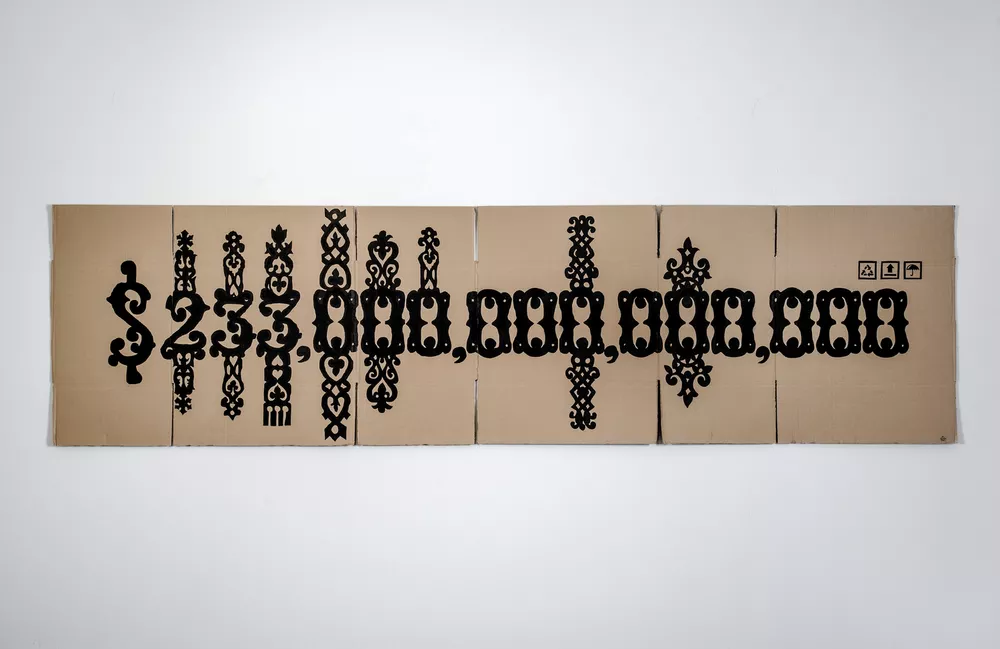

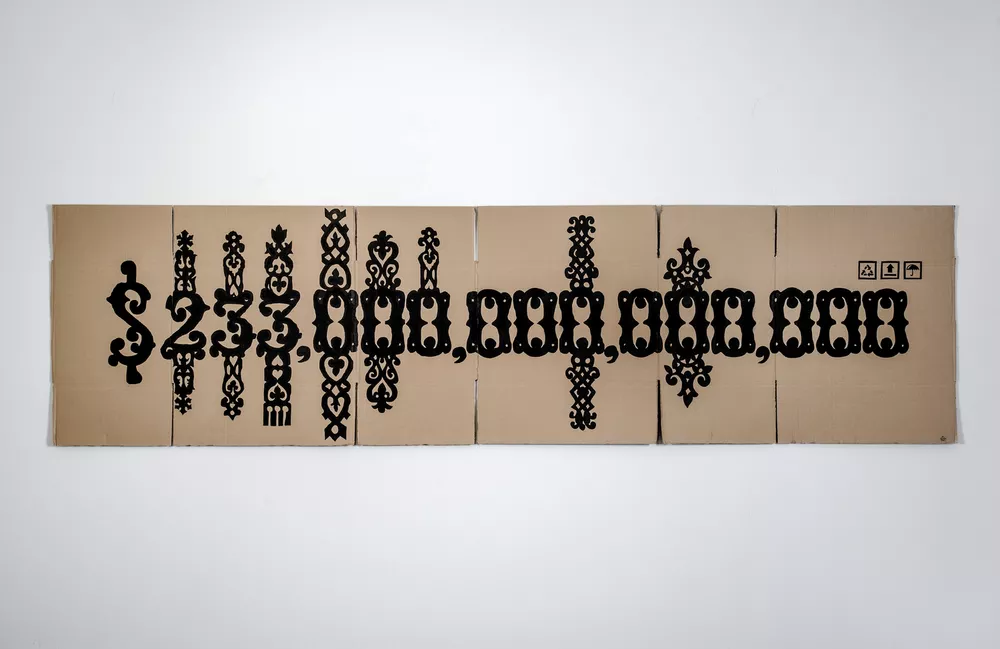

Kölelik Müzesi’ (2015), ‘ Dünyanın Toplam Borcu Olan 233 Trilyon $ Kutsal Bir Sayıdır’ (2016), ya da ‘

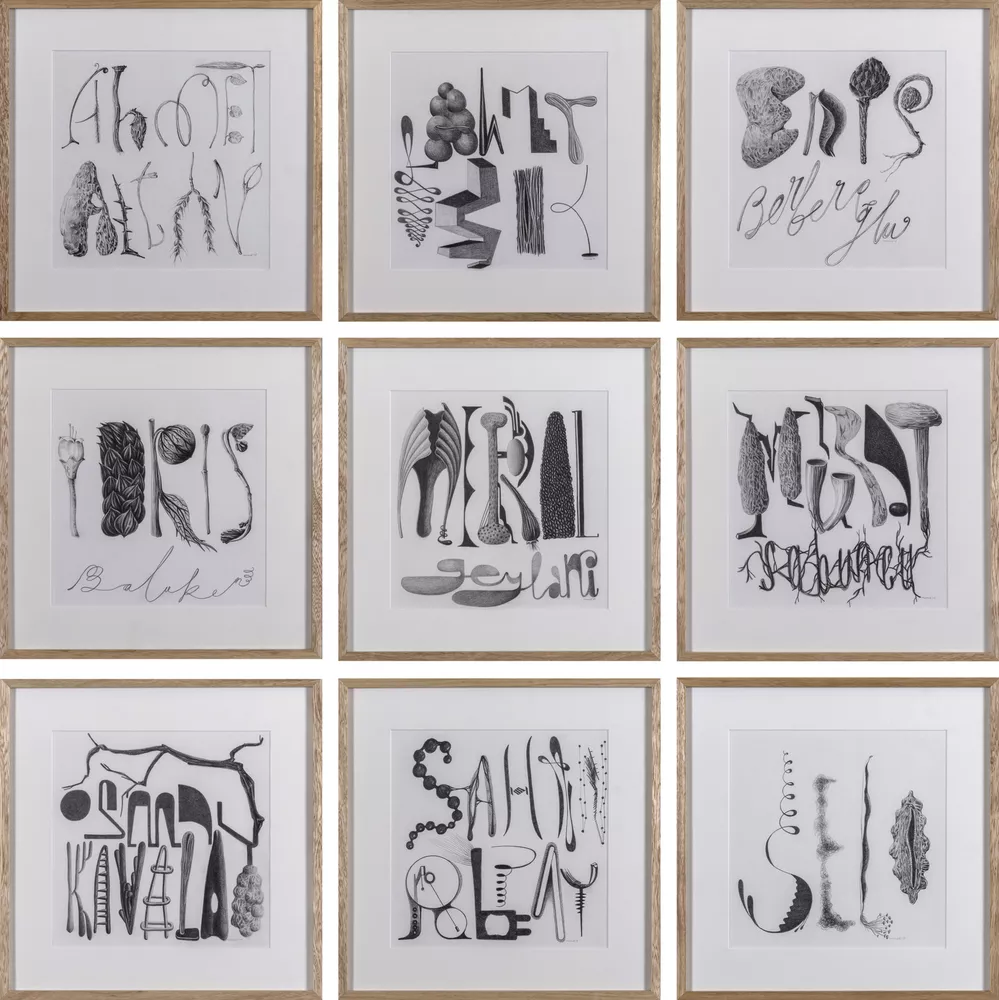

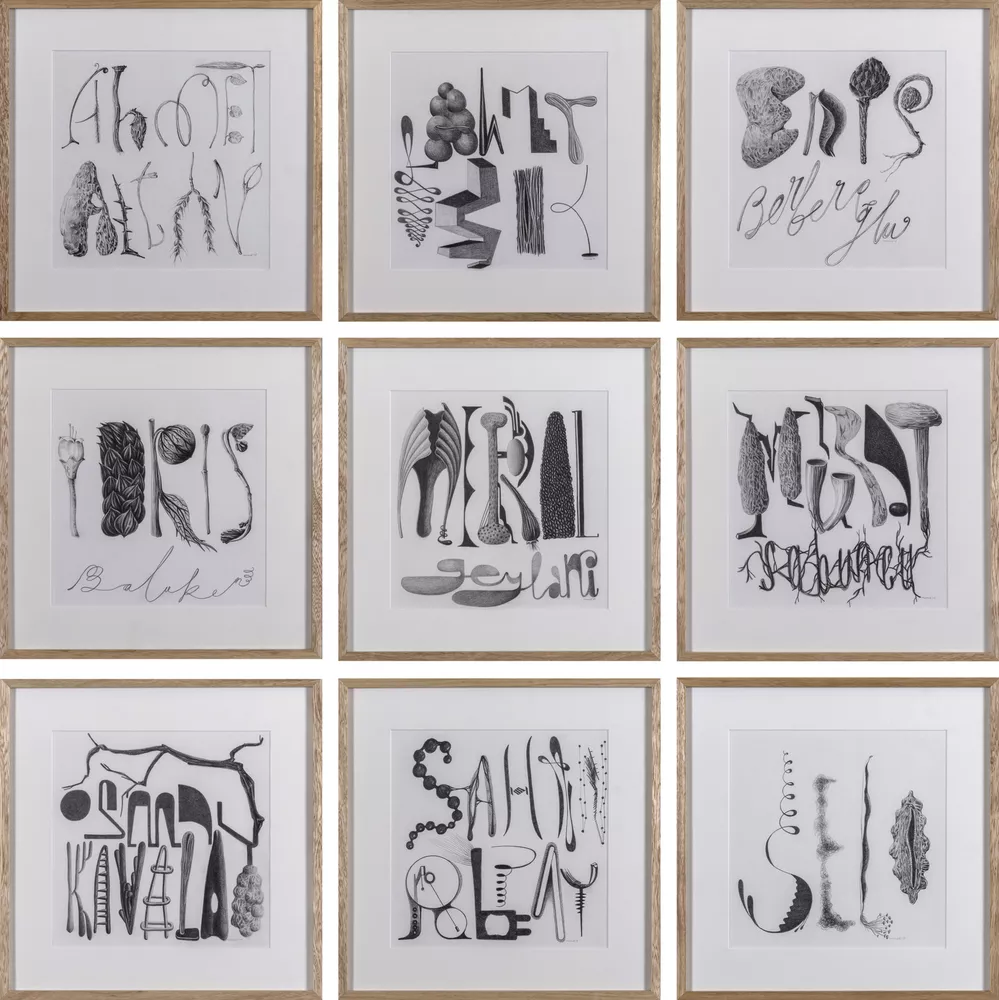

Dünyanın Toplam Borcu Olan 233 Trilyon $ Kutsal Bir Sayıdır’ (2016), ya da ‘ İtaatsizlik Kaligrafileri’ (2015) gibi tekil ve çoğul yapıtlarıyla da plastik üslûp ve metinsel eleştiri açısından omuz omuza tutunuyor.

İtaatsizlik Kaligrafileri’ (2015) gibi tekil ve çoğul yapıtlarıyla da plastik üslûp ve metinsel eleştiri açısından omuz omuza tutunuyor.

Sergide bu yönüyle, sanatçıya ait ‘Bireyi Kitleyi Oluşturma Görevinden Caydırma Kurulu’, ‘Gelecek Zamanın Hikâyesi Bakanlığı’, ya da ‘LGBT Hakları Konseyi’ ve ‘Şeylere Kendi Varlık Nedenlerini Verme Dairesi’ gibi örnekler yer alırken, etkinlik izleyicisine ‘bakma, görme, okuma ve yorumlama’ deneyimi sırasında edebiyat, kavramsal sanat ve bütün-parça arasındaki her türlü hiyerarşik aidiyetle ilişkisini yeniden hatırlatarak, yıkıcı olduğu ölçüde yapıcı bir sorgulama teklifinde de bulunuyor.

Memed’in ‘Ütopik Bürokratik’ levhaları, biçim ve içerik arasında salınan sanat tarihsel ve kavramsal vesayet kavgasına da muzip birer önerme bütünü ortaya koyuyor. Her şeyden evvel, kişiye melankoliden başka hiçbir vaatte bulunmayan bu çalışmalar, izleyici olarak baktığımızı görmeye, üzerine eyleyici olarak bir şeyler katabilmek adına ne kadar meyilli, müsait olabileceğimize, bilinen en medenî enstrümanla, dilin plastik esnekliğinde önermeler sunuyor.

Bu levhalar ‘Allah Vergisi’ hayal gücümüzün birer ‘Algı Levhası’ gibi iş görüyor. Bu ‘özde’ kurumlar, Türkiye’de süregiden, bireysel kimliksizleşme salgınına, zehir etkisiyle şifa olarak dayatılan totaliter kurumsallaşma bağımlılığının, sahiden özgür iradelere devren kiralandığında nelere kadir ve inanır vaziyette olabileceğini sorgulatıyor.

Türkiye. saç tasarımcılarının, güncel fetva kurullarının, karantina sebebiyle iki daire arasında halay çekenlerin, tüketici içgörüleri uzmanlarının ekmek parası kazandığı bir ülke. Bu koşullar altında, hayal gücünü iktidara taşımaya azmeden Memed’in mucidi olduğu bu yeni, iyileştirici, sağaltıcı müdürlükler, daireler, kurullar, konseyler ve şubelerin her biri, kamunun ödünsüz huzur ve sevinci adına 7/24 kesintisiz ‘hezimet’ değil, ‘full hizmet’ vadediyor. Yapıtların her biri birer beyaz yakalı ‘kartvizit’ gibi değil, ‘Art‑Visite’ (Sanat Vizitesi) gibi çalışıyor. İş görüyor. (Vizite, bilindiği gibi ‘hastane hekiminin koğuşları dolaşarak, yatar hastalarını yoklaması’ veya ‘bir muayene için hekime ödenen ücret’ anlamlarına karşılık geliyor.)

Dahası, sanatçı tasarladığı bu hayal terminaline gelen her bir ziyaretçinin de kendi taşıyıcılığı ve kurumsallığına, galeriye eklenen panoyla da davetiye çıkarıyor. Böylece daha da kamusal olmaya yaklaşan sergi, esas ütopyanın, ancak kitlesel devrimci ruhla inşa olabileceği ve her an kendinden gebe kalabileceği fikrini günlük yaşama yeniden, tüm bereketi ile şırıngalamayı başarıyor.

Memed, aşağı bakmaya teker teker alıştırılmaya çalıştığımız bu günlerde, hepimizi kendi yukarı bakma terminaline bekliyor.

Bu da ‘Hürokrasi’ye açık bir davet olma anlamına geliyor.

“Read and tell.”

What we were exposed to in primary school was probably the first bureaucratic order.

We would first memorize things (certainly without anyone hearing), then we would run to the same meaning and ideal by driving our own makeshift words, and also to our actions, if we had luck and courage.

Memorizing something was equal to its owning us, simply keeping us to itself. When we were to be told “show me”, we wouldn’t fall short of delivering it in one breath. The more we remember it, the more we would hold on to it and defend it until we lose ourselves.

We have also felt this dilemma with all the physical and political maps that were presented before our eyes in atlases. Some of us put their index finger directly at their country on these maps, some of us found themselves on different places where they always wanted to go, like an indirect object.

Then this did not end. We began experiencing ourselves neither in full abstraction nor in the intricate bouquet-like of our embodiment, we were torn between images with subtitles, or between “original-dubbing” or “colorful black-and-white” or “live-tape” tides.

Or we always took over a “steering wheel” in Painting, Music and Turkish lessons. We envisioned national yesterdays, seasons, various local, domestic and human traditions, first with lines, then paints, then notes and words, and then we started tolerating their truth. We could not come across ourselves in our music, images, or words.

We always left the gear of reasoning in automatic navigation, we failed reasoning, we had to make up, and we had to replenish.

Memed’s latest series of work entitled “Utopian Bureaucratic” featured in Zilberman Istanbul, brings up a series of directional signs in order to confront us with ourselves again on the painful map of life traffic.

We have a group of “annoyed” words that rebel against dictionaries, saluting Can Yücel, Ece Ayhan, Cemal Süreya, Turgut Uyar, and Orhan Veli. They all promise a content worthy of expression that can be read in several ways. They prioritize conducing towards something, not directing.

Stylistically, these signs with strong voice and roasted bodies which take reliefs and inscriptions behind them, incorporate the increasingly abstract schemes of today’s underground networks or the Art Deco graphic courtesy of modern art.

Memed is increasingly intervening in a poetic way, reaching a sheer conceptual clarity, about how we can get out of the visual, textual, semantic “patterns” and how long we can be alone with them with this series, in which he regards poetry perhaps as the most plastic material known.

Whereas the word pattern corresponds to expressions such as “painting,” “sample,” “specimen,” or “mold” in Ottoman language, it also means “texture” in its common usage today. Here, thanks to this legal personality “pattern,” each in Turkish, Erdener invites each of us to the utopian excavation of a collective, optimistic structure in line with our individual imagination capitals and voluntary participation requests. This gentleman goes in the opposite direction of stereotypes and derives them like in an ivy dream in hanging-signs and they roost in our time and space indecently and indiscriminately.

Utopian Bureaucratic acts in solidarity with Memed’s earlier works such as  Turkey Of The Republic (2010),

Turkey Of The Republic (2010),  1915 (Dedicated to all Armenians living in Turkey) (2012),

1915 (Dedicated to all Armenians living in Turkey) (2012),  Slavery Museum (2015),

Slavery Museum (2015),  233 Trillion $ the Total Debt of the World Is a Sacred Number (2016), or

233 Trillion $ the Total Debt of the World Is a Sacred Number (2016), or  Calligraphies of Disobedience (2015) in terms of plastic style and textual criticism.

Calligraphies of Disobedience (2015) in terms of plastic style and textual criticism.

In this respect, the exhibition includes signs such as the “Committee for Deterring the Individual from Making up a Mass”, “Ministry for Future Tense in the Past”, “LGBT Rights Council” and “Chamber of Submitting Existential Rights to Things”. The event invites the audience to “look, see, read and interpret”, proposing a constructive —as much as destructive— questioning, reminding them of all kinds of hierarchical belongings between literature, conceptual art and meronymy.

Memed’s Utopian Bureaucratic signs reveal a totality of mischievous propositions to the art historical and conceptual ward fight that oscillates between form and content. Above all, these works, which make no promises to the person other than melancholy, make suggestions through the plastic flexibility of language, which is the most civilized means of communication, on how we can tend to see what we look at as a spectator, and how available we can be to add something on it as an agent.

These signs function like a “Perception Board” of our “God’s Gift” imagination. This “essential” institutions make us question what would happen if and when the totalitarian institutionalizing frenzy which is imposed as a remedy but does poison effect for the ongoing individual disidentification in Turkey would be subleased.

Turkey is a country where hair designers, latest-fatwa councils, people dancing halay in between two buildings because of quarantine limitations, and consumer insight specialists earn their keep. Under these conditions, Memed is resolved to bring imagination to power and each of these new, healing, medicinal directorates, chambers, councils, branches that he invented promise us a “full service,” instead of 24/7 non-stop fiasco in the name of uncompromising peace and joy of the public.

Each of the signs fulfills the duty of an “Art-Visite,” instead of a white collar “business card.” (As it is known, visit refers to when physicians walk around to check the condition of patients or to the fee paid to a physician to seek medical advice.)

Moreover, the artist put a board on the gallery wall inviting each visitor who visits this dream terminal to their own transportation and institutionalism. Thus, the exhibition, which is getting closer to being even more public, manages to inject the idea that the main utopia can only be built with a mass revolutionary spirit and that it can conceive at any moment into daily life with all its blessings.

Memed is waiting for us all at his look-up-terminal at a time when we are expected to get used to looking down.

And this means an open invitation for ‘Freecracy’.